Have you ever heard the story of The Hundredth Monkey?

While on holiday over Christmas, I spent some time in a delightfully cursed second-hand bookshop, the construction of which resembled the sort of maze one might use to trap unsuspecting medical rats. As I was browsing the science fiction racks for unhinged, 1970s-era pulp, a hand passed me a small book. The yellowed paperback cover was decorated with an expanding blot pattern, an alarming statement about nuclear war at the centre. On the back, the text flitted back and forth between hyperactive new-age terminology and talk about the end of the world. It told me my life and well-being were at stake. I couldn't leave the haunted book labyrinth without this strange object.

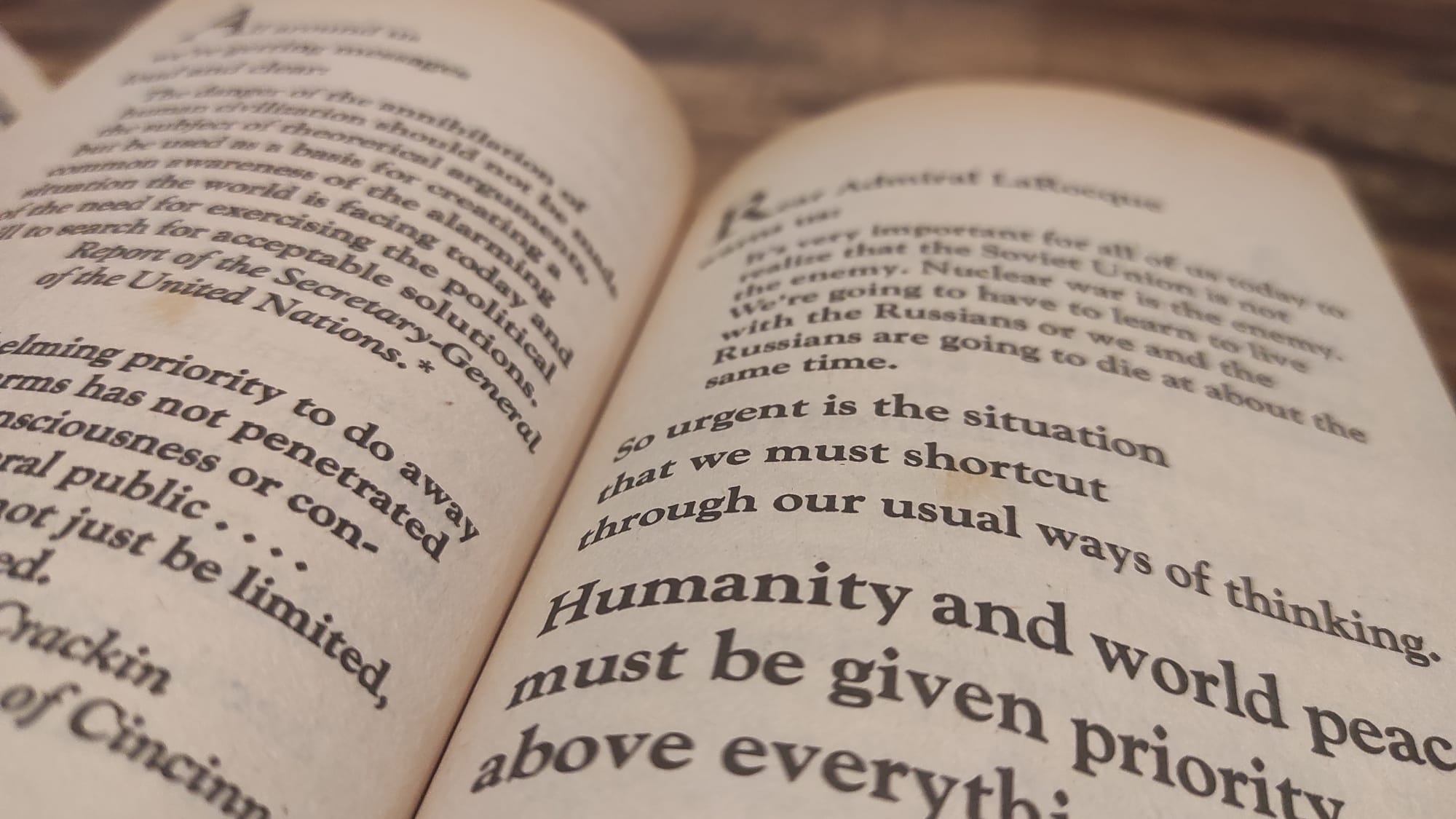

The Hundredth Monkey is an immediately curious artefact. It's only 176 pages, most of which contain less than fifty words; roughly every second page has a small illustration off to one side; it is rife with detailed footnotes and awash with exclamation points. Much of the prose is written in short, sharp lines, like poetry.

Upon taking the item home, I found that the whole book is constructed as a frantic call to action against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Published in 1981 (or 1982, or 1984, depending on the source consulted), THM was conceived and crafted during a tense period of the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union; a period in which it wasn't uncommon to reflect on the very real chance of the world being destroyed by a very quick and horrible nuclear conflict. That alone certainly makes it a worthwhile topic for discussion.

How this book goes about communicating its message, however, is fascinating. The tone is deeply serious, with frequent references to academic papers, recounting of historical events and quotes from wise heads. Despite this, the prose resembles a whimsical—if deeply manic—self help book. Multiple pages are dedicated to explaining the disturbing realities of radiation poisoning, but equal time is given to self-actualising in order to boost your mental flexibility. Lengthy quotations on ecological concerns sit a reader's glance from 30-point text screaming about the power of love and cooperation. Written entirely in capital letters, of course.

One hundred monkeys walk into a war...

The hundredth monkey effect, to which the book—The Hundredth Monkey—refers, is an idea popularised in the 1970s relating to the spread of new ideas. The claim is that when a critical number of individuals exhibit new behaviour or learning of a new concept, the knowledge will quickly become ubiquitous. The name and idea come from a team of Japanese scientists studying a troop of monkeys on the island of Kōjima in the 1950s. The troop was isolated from other monkey societies and therefore provided an excellent study group for monkey behaviour.

Part of these studies involved the scientists dropping sweet potatoes and wheat on the beach to see what the monkeys would do. At some point one monkey began to wash the sweet potatoes in the water, and this behaviour was slowly—by social means—spread to the other monkeys in the group. So far this is relatively normal animal behaviour, and the original team seemingly catalogued plenty of interesting information.

Enter a man named Lyall Watson. In a 1975 foreword to anthropologist Lawrence Blair's book Rhythms of Vision, Watson published a story making some altogether wilder claims about the Kōjima study. He put forth that by 1958 the potato washing behaviour had essentially become part of the collective consciousness of the monkeys as a result of a critical mass of smart monkeys. Enough monkeys had learned to wash potatoes that now every monkey in that society automatically knew how to wash a potato, even if they had never seen the behaviour demonstrated. Watson expanded on this by stating that monkeys in troops across the water on other islands had picked up this behaviour via some sort of Jungian osmosis.

Keyes picked up the more fanciful and supernatural version of the story, and used it as the central thrust of his book, presenting it as an inspiration for affecting personal and societal change. Partly due to Keyes wrapping his book around it, the hundredth monkey effect became quite popular among New Age types, as you might imagine; collective brain waves that travel through the air and infect entire populations sounds like a dream story for self-help types and fans of Actual Magic.

The phenomenon's popularity in New Age circles is inversely proportional to its reputation in scientific fields. A cultural event horizon where animals (or humans) transmit learning to collective cloud storage has been widely debunked, and many of the attributions linked to such effects were easily explained using our existing knowledge of how animals learn new skills. There weren't even 100 monkeys in the original group!

It has been argued, in fact, that Keyes popular misrepresentation of the Kōjima monkeys in this very book led to many attempts to discredit the original study, which made no claims about long-range brain telegrams or morphic behavioural fields.

Peace, love and regular donations

There's a whiff of cult behaviour to it, if I'm being honest. The cloying earnestness and inflamed commentary about the state of the world brings to mind some of the more sinister organisations in human history. Scientologists' desperate need to convince strangers that they have stress gremlins, Charles Manson's talk of an inevitable and imminent race war, the mass weddings of the Moonies—designed to create 'pure' families in Jesus' name.

Some of the same red flags one might have seen in reading materials or propaganda for these groups are hinted at in The Hundredth Monkey. Before the foreword, you can see a list of other vital books by Ken Keyes Jr., all of which have the air of harmless benevolence often associated with cult leaders. A Conscious Person's Guide to Relationships; Prescriptions for Happiness; and Handbook to a Higher Consciousness seem to stink of that warm, sickly sweet manipulation style that has drawn in many throughout history. The book loudly states it is not copyrighted and cheaply priced specifically so you can spread the word to others.

What struck me as the most superficially discrediting part of the book was how many times it mentioned something called The Vision Foundation. The Hundredth Monkey is published by Vision Books, which was the publishing arm of the Foundation, as far as I can tell.

You will not find any evidence that The Vision Foundation existed in an easily accessible place. Keyes' own Wikipedia page makes no mention of it, but does contain significant details about the Ken Keyes College, where enrolled students could learn about his Living Love method of navigating life. In the appendix of The Hundredth Monkey, however, offers several ways to contribute to Keyes, the foundation, and the cause. Other books give you "...the blueprint for becoming the master of your mind..."; something called ClearMind Trainings allow you to attend weekend workshops about loving yourself; most importantly, a tax-exempt donation of a mere 10% of your income will help the Foundation "create a safer world."

Not entirely bananas

Even though it's steeped in bizarre, pseudo-religious terminology and marked with many of the hallmarks of a philosophical con-job, The Hundredth Monkey has a certain air of authenticity that sticks in the brain. The thoughts and ideas Keyes speaks about feel genuinely thought through and are supported, mostly, by decent sources. And I'm just going to say it: nuclear war is bad.

Do I want to join a strange cult about it, forfeiting a percentage of my income? Probably not. But there is something admirable about someone feeling so nakedly passionate about an issue that they believe concerns the survival of humanity. Reading the book gives you a sort of jolt of cognitive dissonance, with logical messages like "weapons of mass destruction are bad" wrapped in a presentation style usually reserved for convincing an audience that cheap bags of crystals can cure boneitis.

The quirky madness of it brings to mind a more modern creator, equally prone to unusual communication styles and equally passionate about the threat of nuclear proliferation. I'm just saying that Hideo Kojima would probably think this book is really cool. And he'd make a new character called Nuclear Monkey, who would steal a Russian bomb and use it to build a walking battle tank so he could prove a point about diplomacy to his dad.

The Hundredth Monkey undoubtedly taught me some things, and changed my way of thinking; not, perhaps, in the way it wanted, but it left a trail through my cognition nonetheless. Without this book, I wouldn't have discovered that the United States Air Force lost a nuclear bomb off the coast of Georgia in the 1950s, or that it still hasn't been found. I also wouldn't know that Ken Keyes Jr. experimented with mescaline and found it induced a seemingly endless orgasm that cured him of being a sex addict. Being forced to engage with the realities of nuclear conflict at a time in history where it suddenly seems dangerously realistic all over again probably isn't such a bad thing, either.

Maybe there's something to take away from the hundredth monkey effect in the modern day, too. Gifting people magic new abilities through the collective unconscious might be absolute hogwash, but we absolutely do now live in a world that is more connected than Ken Keyes Jr. could possibly have imagined. Social media provides a method of instantly transmitting concepts to hundreds of thousands of people; if you can make a whole demographic all agree on which meme is funny today, why couldn't you do the same for attitudes about nuclear weapons? Or climate change? Or fascism?

After finding the book incorrectly shelved within the science fiction section of a liminal bookstore at the other end of the country, maybe I've become the hundredth monkey.

Member discussion